Anyone with a sense of recent online poker history knows the turbulence that surrounded a few prominent companies’ efforts to continue large-scale services to United States players, following the passage of the 2006 Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act (UIGEA). That the playing of online poker by Americans was technically illegal, though it was confirmed six years later in a Justice Department clarification of the Wire Act, the original US law on which all subsequent federal gambling statutes are based.

Anyone with a sense of recent online poker history knows the turbulence that surrounded a few prominent companies’ efforts to continue large-scale services to United States players, following the passage of the 2006 Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act (UIGEA). That the playing of online poker by Americans was technically illegal, though it was confirmed six years later in a Justice Department clarification of the Wire Act, the original US law on which all subsequent federal gambling statutes are based.

Instead, the UIGEA was a surreptitious strike created by gambling opponents to curtail the large-scale of money to and from online sites via instantaneous forms of transmission. UIGEA’s first direct victims, other than UK-incorporated sites that voluntarily left the US market, were online payment processors such as FirePay and NETeller, the latter paying extensive fines and settlements after its Canadian founders were indicted.

The war was on, and online sites such as PokerStars and Full Tilt still coveted the immediacy of online deposits and withdrawals, since they allowed a more casual type of poker player to play without waiting days or weeks for paper-check deposits to be processed and confirmed. Thus began a cat-and-mouse game between the largest US-facing sites and agencies of the US government, including the DOJ, FBI and FDIC.

That cat-and-mouse game lasted for nearly five years, until the April, 2011 “Black Friday” indictments that forced Poker Stars, Full Tilt and the Cereus Network (Absolute Poker / UltimateBet) from the US market. All three sites would eventually be shown to have participated not in the offering of online poker, which even in this interim period was of debated legality, but of something more clearly illegal — the manipulation of certain elements of the US banking system in an increasingly fruitless attempt to keep those instantaneous online spigots open.

One of the major developments in the five years between UIGEA passage and Black Friday was the rise and fall of Intabill, an Australia-based payment processor, the brainchild of young entrepreneur Daniel Tzvetkoff. The high-flying Tzvetkoff thought he had the world on a string when the major poker-processing operations directed to and from the post-UIGEA United States fell into his lap, but Intabill’s heyday lasted only a year.

Intabill’s early-2009 collapse resulted in the loss of tens of millions of dollars of poker-site money that ultimately disappeared from the business. Shady processors were part of how firms such as PokerStars and Full Tilt kept servicing the US and providing those instantaneous deposits and withdrawals, and they grew shadier as time went on.

Intabill wasn’t the only such processor forced out of business; there were several. But Intabill was the largest, with Full Tilt filing suit against Intabill, Tzvetkoff and company co-founder Sam Sciacca in June of 2009 for $52 million, the first time Intabill’s name flashed across the poker public’s knowledge. Given that the firm also did transactions for Absolute, the total that disappeared down the Intabill sinkhole was likely $100 million or more.

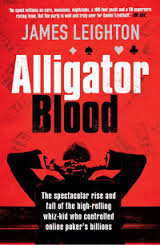

What became of that money is one of the questions not really answered in James Leighton’s new book, Alligator Blood. Leighton’s book is, for the most part, a first-person account of the rise and fall of Intabill, as told in large part by Tzvetkoff himself. The book is fleshed out with plenty of anecdotal accounts from Sciacca, Tzvetkoff’s one-time partner, who laid the blame for Intabill’s shoddy operation at Tzvetkoff’s feet and ended up suing Tzvetkoff himself for another AUD $100 million. (Disclaimer: The book also includes informal interviews from a half dozen or so poker figures who flesh out the poker scene in general, but were not directly connected with Intabill. This writer is one of those interview subjects.)

What became of that money is one of the questions not really answered in James Leighton’s new book, Alligator Blood. Leighton’s book is, for the most part, a first-person account of the rise and fall of Intabill, as told in large part by Tzvetkoff himself. The book is fleshed out with plenty of anecdotal accounts from Sciacca, Tzvetkoff’s one-time partner, who laid the blame for Intabill’s shoddy operation at Tzvetkoff’s feet and ended up suing Tzvetkoff himself for another AUD $100 million. (Disclaimer: The book also includes informal interviews from a half dozen or so poker figures who flesh out the poker scene in general, but were not directly connected with Intabill. This writer is one of those interview subjects.)

For all the good information in Alligator Blood, the demise of Intabill is the one part of the story where the truth never quite emerges. While Full Tilt’s lawsuit against Daniel Tzvetkoff and Intabill was the first time Tzvetkoff’s name made headlines, it wasn’t the last. Tzvetkoff, even by his own admission in Alligator Blood, lived way too freely and highly, purchasing an Australian Gold Coast mansion, financing a race team, and getting himself in the headlines of Australian social and business columns way too often for the comfort of his business partners, including PokerStars founder Isai Scheinberg.

Once Intabill grew to a certain point in terms of corporate revenue, the firm was required by Australian law to hire a Chief Finance Officer (CFO), provide proper financial reports, and conduct periodic audits. Tzvetkoff wanted none of it, not quite admitting to Leighton in Alligator Blood that he cooked the books, but trying unsuccessfully to get rid of the CFO that Sciacca had hired. Tzvetkoff preferred to shoot from the hip and make business deals in a nightclub over a bottle of high-priced liquor, and his looseness in selecting American business partners that eventually caused Intabill’s collapse.

Tzvetkoff eventually got in bed with some American crooks, who were busy grinding out a profitable living through unsavory payday-loan operations and similar bottom-feeding operations, and soon after joining that scene, and out-of-his-league Tzvetkoff was soon outmatched. That led to Intabill being stolen from underneath Tzvetkoff and Sciacca, and that part of the tale, at least, is believable. As for the money, that’s another story.

We’ll have more on Intabill’s demise in this tale’s next installment.

100% up to $3,000 Bonus

Bovada is our most recommended ONLINE CASINO and POKER ROOM for US players with excellent deposit options. Get your 100% signup bonus today.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.