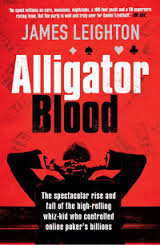

If there’s a surprise buried within the pages of Alligator Blood, British author James Leighton’s recounting of the tale of the meteoric rise and fall of Australian payment processor Daniel Tzvetkoff and his Intabill operation, it’s that as early as 2008, major US-facing online poker sites such as PokerStars and Full Tilt should have had knowledge of tribal processing operations that could have provided a convenient “black box” solution to moving money to and from US customers.

If there’s a surprise buried within the pages of Alligator Blood, British author James Leighton’s recounting of the tale of the meteoric rise and fall of Australian payment processor Daniel Tzvetkoff and his Intabill operation, it’s that as early as 2008, major US-facing online poker sites such as PokerStars and Full Tilt should have had knowledge of tribal processing operations that could have provided a convenient “black box” solution to moving money to and from US customers.

The implications are immense. Had these sites not resorted to tried-and-failed methods of processing transactions for their American customers, using the same old crooked processors who were already being investigated by US federal agents, then a shift to tribal processing could have occurred. With processing options distributed over several such processors, such handling of transactions likely represented the only viable long-term option available to these site in the post-UIGEA era, effectively taking advantage of tribal sovereignty claims to shield the inner workings of the business from banking investigators’ probing questions.

In other words, Black Friday was absolutely guaranteed to occur, given the nature of the processing options then being used. However, it’s possible that by shifting the processing load to such protected tribal operations, Black Friday itself could have been avoided.

Who bears the ultimate responsibility for giving away the virtual ranch? There’s a host of likely candidates, none larger than the poker-site execs themselves. From PokerStars’ Isai Scheinberg to Full Tilt’s Ray Bitar and Howard Lederer, and including a couple of prominent gaming attorneys who kept pushing the sites to explore the same old processing options, the whole episode represents such a case of willful ignorance of United States legal concerns that it’s hard to take these gaming execs too seriously in retrospect. They simply didn’t know what they were doing.

Another peek inside the pages of Alligator Blood shows the possibility of tribal processing being raised. Both Tzvetkoff’s Intabill operation and the US-based services of Impact, Trendsact and other companies, led by John Scott Clark and Curtis Pope, continually struggled against an overriding problem: They needed larger ACH (Automated Clearing House) processing capabilities. The problem was the nature of the gambling transactions themselves, which frequently included amounts in small, round numbers that stood out when compared to other forms of payment processing.

Tzvetkoff and Intabill sought out Clark and Pope precisely because of their claims to be able to provide larger ACH pipelines, and thus fulfill the demand for immediate processing that the online sites desired. But Clark and Pope promised more than they could ultimately deliver.

In Chapter 20 of Alligator Blood, Leighton reveals that part of John Scott Clark’s growing payday-loans operation was to employ the “rent a tribe” approach and enlist a tribal processing partner, thus to be able to take advantage of tribes’ sovereign status and do an end-around of various usury laws which designed to protect consumers from the exorbitant interest rates charged. Leighton includes one quote claiming that the annualized interest rates on such short-term loans could exceed seven hundred percent, with the loans jammed down consumers’ throats by Clark’s and Pope’s ruthless operations.

One of the unexplained connections in Alligator Blood lightly hints that one of the reasons Tzvetkoff and partner Sam Sciacca couldn’t get their $35 million back from Clark and Pope is that that pair — Clark in particular — were already misappropriating the funds themselves. Clark’s Impact operation subsequently fell apart, with jilted investors only later discovering that Clark likely walked away with tens of millions, while using a fresh-out-of-school junior accountant (who was easily intimidated) to unknowingly cook the books.

But that was later. In 2008, the plan was to get tribal processors onboard to help with the overbearing ACH needs. Clark had a strong business with Chief Martin “Butch” Webb of North Dakota’s Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, and Webb also controlled a tribal bank, the Western Dakota Bank.

Webb and his Western Dakota bank were set to join the processing, and then the separate troubles facing Clark’s and Pope’s payday-loan operations began to emerge. Amid all that, the Western Dakota processing proposal collapsed. Clark subsequently secured a different tribal processor, in Montana, for a short period of time, before Impact itself folded under legal pressure from jilted investors.

As Leighton wrote, paraphrasing Tzevtkoff, “If an American Indian reservation could operate under its own laws and remain immune from prosecution in the payday loan world, then why shouldn’t that also apply to online poker?”

That question, indeed, has never been answered. It is believed that Clark and Pope used the promise of tribal processing as part of their plan to steal the PokerStars / Intabill business from Tzvetkoff and Sciacca. Therefore, Stars’ Scheinberg had to have been cognizant of the tribal processing opportunity by this point at the latest.

All of the major US-facing sites should have been aware of the possible tribal solution, led by the example of Canada’s Kahnawake Gaming Commission, which to this day maintains extensive internet-service operations from atop a major Internet pipeline just outside Montreal. The online e-wallet UseMyWallet was a tribal-based online payments site, as an example; it’s just an example of the type of sites that could have flourished, had poker-site execs made some different decisions.

Reading between the lines, it seems that sites such as PokerStars and Full Tilt closed their minds to tribal processing after Curtis Pope’s Impact operation collapsed. Quasi-legal considerations aside, it’s clear from a business sense that it was exactly the wrong decision. Instead of pursuing a new opportunity that promised “black box” processing and a protection of sorts from federal prosecution, Stars, Tilt and (to a lesser extent) AP opted to keep continuing business with the same pack of shady Anglo crooks they’d used in the past. That led to the whole SunFirst Bank fiasco, in which the sites quite openly conspired with certain processors to circumvent US banking laws.

The saddest thing may be that they never needed to do so, had their foresight and knowledge of tribal law been better. Some of what tribal businesses do under the shield of “soveriegnty” is in of itself despicable — the “rent a tribe” businesses of payday-loan processing being a fine example. Still, the major US-facing sites could have explored that route; if the poker itself was legal, as they always claimed (and which was affirmed in a late 2011 DOJ opinion), then they would have been on the most secure legal ground they could have found since the UIGEA’s passage in 2006.

Instead, they blew it. And online poker options for US players are much weaker as a result.

What happened next is u

100% up to $3,000 Bonus

Bovada is our most recommended ONLINE CASINO and POKER ROOM for US players with excellent deposit options. Get your 100% signup bonus today.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.